Like many of life’s great achievements, the International Association of Lyceum Clubs began as a dream—the dream of a young woman and a small group of her friends, living in London in the early years of the twentieth century. The young woman’s name was Constance Smedley and she and her friends, Christina Gowans Whyte, Elsa Hahn, Violet Alcock, and an American, Jessie Trimble, were members of the Writers Club.

By 1902, women were moving tentatively into the male professional world and it is not unrealistic to suppose that Constance and her group, observing men, comfortably ensconced in their London Clubs, began to wonder “Why not Women?”

As they talked among themselves, the group began to envisage, “an ideal Club [for women] with its branches in all countries of the world and [a] chain of Clubhouses” in the world’s chief capitals. In essence, they had foreseen the present world of Lyceum.

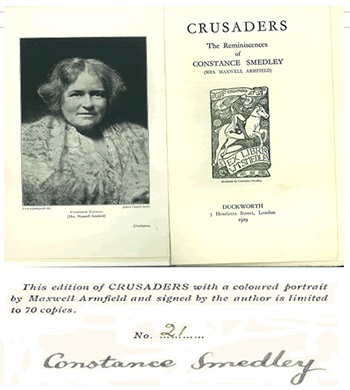

Constance was chosen by her “chief coadjutors,” as she liked to call her four friends, to approach the Committee of the Writers Club with such an idea. In her autobiography Crusaders, she tells how she was asked by the Committee of the Writers Club, “And who is to organize this?”

Full of youthful confidence, and perhaps a touch of bravado, she replied, “I will.” To her “amazement, disgrace and shame,” the Committee turned her down.

However, this rebuff motivated, rather than deterred Constance. The decision was taken by the group to “start a new Club,” and although the group had no money, they were determined to pursue their dream. They therefore decided that they must first form a Provisional Committee. As their proposed Club was then intended only for “writers and illustrators,” Constance forwarded out the first letters, sixty in all, to prominent women in these fields. Only two offered their support.

Still undaunted by the lack of interest, she wrote back again to those who appeared to refuse regretfully, and also to other women she hoped might be interested. Slowly a Provisional Committee began to take shape.

At this stage, they began to realise that if there was to be a Club, there must be a Clubhouse in which to meet. Constance and her friends turned to her father, Mr W. T. Smedley, for help. A successful businessman, he was experienced in financing and the purchase of property, and blessed with a modern point of view. Mr Smedley believed women were entitled to “a professional life and full freedom of development” and he promised to help them find a suitable building. However, like all the best fairytales—and in a way, the founding of the first Lyceum Club, does have some of the aspects of such a tale, there was a condition.

First, the Provisional Committee must secure a thousand members at an annual subscription of a guinea (twenty-one English shillings) each. Even this prospect did not dissuade Constance from her objective. As she says in her autobiography, Crusaders, “The oddest part about the founding of Lyceum was that in all the discouragement of the start, it never occurred to me to lose faith for one moment in the idea.” So there were more letters and more interviews.

The name, “Lyceum,” was suggested by the American Jessie Trimble for the new Club. In the United States, the name was known as representing a centre for lectures and discussions, while in Europe, where the term had originated many centuries ago in Athens, the term was equally understood.

By then the group had decided that its membership must be open to more than just writers and artists. Constance Smedley’s sister suggested

women with academic qualifications be accepted, and a third group was included, “wives and daughters of distinguished men.”

Finally, the group decided it was necessary to have a recognisable, well-respected woman to lead this new Lyceum Club. One of the group suggested Lady Frances Balfour, daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Argyll, and the sister-in-law of the British Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour. Lady Frances, a fluent speaker, was devoted to women’s issues and though she spoke often at suffragist public meetings, she was not in favour of violent protests. Although she had decided to refuse the invitation to lead the Provisional Committee, Lady Frances arranged to meet with Constance. As she listened to the plans for the new Lyceum Club, her attitude changed and she decided to accept their invitation to become the first Chairman of the Provisional Committee. For fifteen years, she served as Chair of the Executive and President of the Club. Lady Frances had been a superb choice.

Finally, the group decided it was necessary to have a recognisable, well-respected woman to lead this new Lyceum Club. One of the group suggested Lady Frances Balfour, daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Argyll, and the sister-in-law of the British Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour. Lady Frances, a fluent speaker, was devoted to women’s issues and though she spoke often at suffragist public meetings, she was not in favour of violent protests. Although she had decided to refuse the invitation to lead the Provisional Committee, Lady Frances arranged to meet with Constance. As she listened to the plans for the new Lyceum Club, her attitude changed and she decided to accept their invitation to become the first Chairman of the Provisional Committee. For fifteen years, she served as Chair of the Executive and President of the Club. Lady Frances had been a superb choice.

Soon it became evident, that 1000 members would be forthcoming for the new London Lyceum Club. The first election notices were issued in March 1903; the new Clubhouse followed a year later in Piccadilly.

1. This history is based on material contained in the following book: Constance Smedley, Crusaders: The Reminiscences of Constance Smedley (Mrs Maxwell Armfield) (London: Duckworth, 1929).

1. This history is based on material contained in the following book: Constance Smedley, Crusaders: The Reminiscences of Constance Smedley (Mrs Maxwell Armfield) (London: Duckworth, 1929).

IALC

IALC Morrinsville Lyceum Club

Morrinsville Lyceum Club Otorohanga Lyceum Club Inc.

Otorohanga Lyceum Club Inc. Tauranga Lyceum Club

Tauranga Lyceum Club Te Awamutu Lyceum Club Int. Inc.

Te Awamutu Lyceum Club Int. Inc. Te Kuiti Lyceum Club

Te Kuiti Lyceum Club Te Puke Lyceum Club

Te Puke Lyceum Club Whakatana Lyceum Club

Whakatana Lyceum Club